Created: 06 July 2020 / Finished: xx xxx 2020 / Modified: xx xxx 2020

Written by Scottish economist Adam Smith in 1776, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, often abbreviated simply to The Wealth of Nations, is considered the beginning of classical economic theory.

Smith spent 10 years writing Wealth of Nations and it shows. The book provides extreme detail and explanation of his arguments and delves into a variety of topics.

Wealth of Nations was well-received by many. Samuel Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and even Karl Marx,

Smith's thesis of the first chapter is relatively simple:

"Division of labor is the great cause of its increased powers"

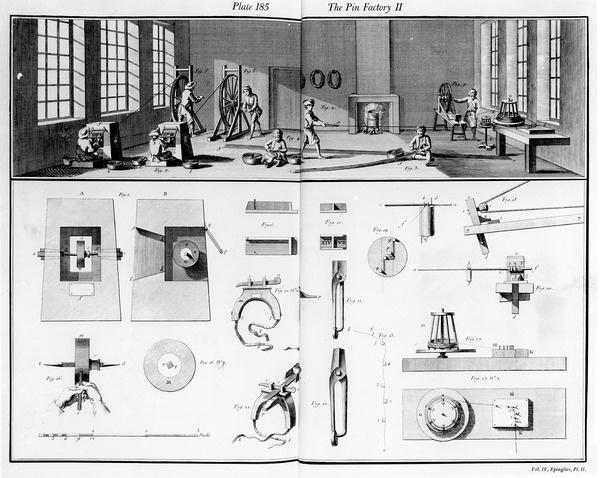

To exhibit the division of labor, he uses the pin factory as an example. There are "about eighteen distinct operations" to making a pin, and the most efficient method is to have one individual per distinct operation (Smith concedes that sometimes one man may head multiple operations). This proves efficient for a two reasons:

This idea is similar to the modern-day assembly line. Instead of having to work on multiple processes and spend valuable time transporting the product to and from sites, the line does the transporting and workers only focus on one operation.

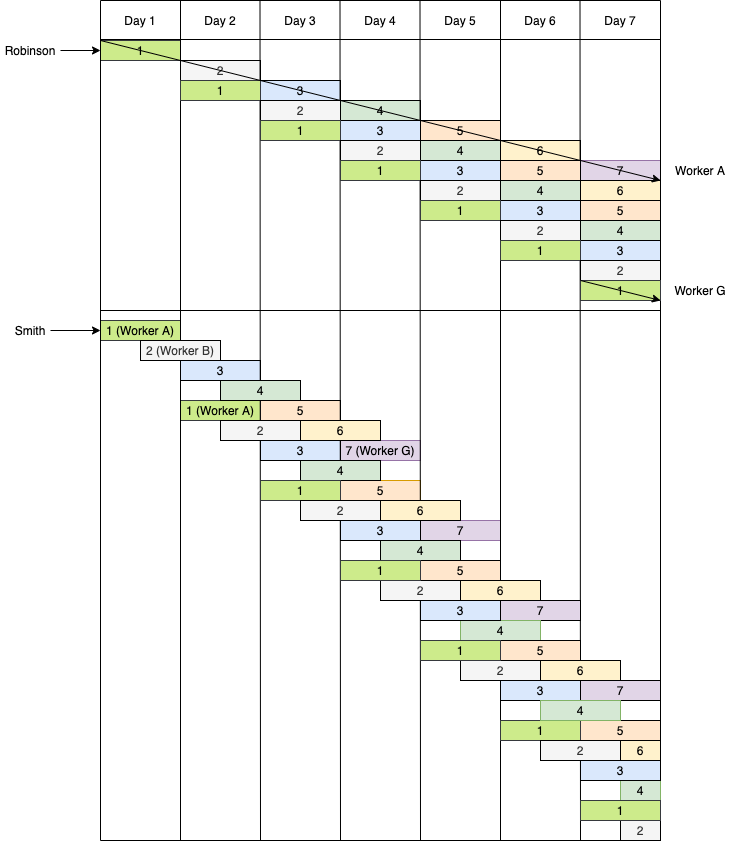

Joan Robinson refutes Smith's division of labor argument in her An Introduction to Modern Economics by stating that a single worker can easily divide the 18 operations over 18 days to produce the same output as 18 different workers over one day. (See this post by Dr. Cameron Murray for specific quotes.) This argument only makes sense over a long period of time. In the short-term, because a complete product only occurs after one full product cycle, Smith's original method of overlapping produces faster results. But as seen in the Robinson's method, product sets will be completed every day after Day 7, whereas with Smith the first complete set is finished on Day 4 and one will be completed every day thereafter.

What Robinson's model does not account for is skilled labor, where a large degree of expertise is required for a specific area. Take semiconductor fabrication (creating computer chip from their elemental materials, like Si and Cu). There are four main processes: deposition, etching, modification, and patterning. Within these are hundreds of subprocesses and nuances that take years to learn, requiring a career specialization. There are many cases of engineers being in one process group for 20-30 years and still learning things about the process. With fields like this it is not worth it for the employee or employer to generalize their skills.

Smith proposes three reasons as to why division of labor outputs so much more:

Division of labor is limited by the "extent of the market", or, put mathematically, the number of positions divided by the working population. If the quotient is greater than 1, then at least one individual will have to fill two roles in his community. If less than 1, at least one position will have two individuals filling it (whether working together or against each other in competition). Smith uses the Scottish Highlands as an example:

"In the lone houses and very small villages which are scattered about in so desert a country as the Highlands of Scotland, every farmer must be butcher, baker and brewer for his own family. In such situations we can scarce expect to find even a smith, a carpenter, or a mason, within less than twenty miles of another of the same trade. The scattered families...must learn to perform themselves a great number of little pieces of work"

Once everyone has chosen their job, some type of exchange system must be created to facilitate trade. After all, the nailer needs meat and the butcher needs nails; the farmer needs tools and the blacksmith needs bread; and so on. The concept of a common currency is thus the logical conclusion to this need, for the nailer's products may be very valuable to the blacksmith, but not vice versa. Currency overrides this inequality. (Keep in mind that currency ≠ money. "Currency is a medium of exchange", i.e., U.S. dollar bills, while "money is a store of value".)

Currency has not always been paper. Cattle, salt, shells, tobacco, and even sugar have been used as currency. These progressed to metals, such as copper and gold, due to their being both easily divisible and combinable (you can't split an oxen and it still be useful), not diminishing in quality over time, and ability to retain value (gold has been valuable for as long as humans have been around). The problem arises with verifying the metal's authenticity. How does one know its legitimate, both in weight and quality? One could easily disguise the exterior of a worthless metal (or chocolate) with gold and claim it's all gold. Gold's density is 19.3 g/cm3, so taking off even a small amount decreases its value significantly, requiring accurate scales to prevent fraud.

What does "value" really mean? Smith gives two opposing, yet complementary, definitions:

"The word value...has two different meanings, and sometimes expresses the utility of some particular object ["value in use"], and sometimes the power of purchasing other goods which the possession of that object conveys ["value in exchange"]. ... The things which have the greatest value in use have frequently little or no value in exchange; and on the contrary, those which have the greatest value in exchange have frequently little or no value in use."

with corresponding examples:

"Nothing is more useful than water: but it will purchase scarce anything ... A diamond, on the contrary, has scarce any value in use; but a very great quantity of other goods may frequently be had in exchange for it."

Smith considers labor to be the source of value:

"The value of any commodity...to the person who possesses it...is equal to the quantity of labor which it enables him to purchase or command. Labour, therefore, is the real measure of the exchangeable value of all commodities."

It's important to note that "quantity of labor" does not necessarily mean time spent on the task, for "there may be more labor in an hour's hard work than in two hours easy business". Implied in this statement is the quality of labor, another important factor in determining the value of a commodity. Money is then used as the estimator of value in exchanges, rather than a direct exchange between products of two individuals' labor.

Two common terms in economics are real and nominal. The nominal price is based off the value of money, i.e., gold and silver, and fluctuates regularly. The real price is based off the constant value of labor, where the consistency in value is only viewed from the laborer's perspective; the baker may not value the blacksmith's tools as much, yet the blacksmith worked just as hard as always to produce them. (Hint from Smith: whenever renting to another, ask for payment in corn, not money—you'll get more value! You can also trade corn.)

What Smith neglects to consider is just how much the value of labor can decrease due to technological innovation. Farmers, who are starting to use more autonomous vehicles (see inside of a tractor cab here), now have little need to operate machinery themselves—instead they can spend the time analyzing the data the machine produces and improve on it that way. Labor in the traditional sense is almost entirely eliminated.

So what contributes to the price of an object/service? Why does corn cost so much when it is seemingly easy to plant and harvest? Smith proposes three components of price: "rent, labor, and profit", with any other possible components being absorbed into one of those three. Examples are given:

"In the price of flour or meal, we must add to the price of the corn, the profits of the miller, and the wages of his servants; and the price of bread, the profits of the baker, and the wages of his servants; and in the price of both, the labor of transporting the corn from the house of the farmer to that of miller, and from that of the miller to that of the baker, together with the profits of those who advance the wages of that labor."

Determining said price is done simply by supply and demand. If there is small supply and the demand is high, the price will increase above its natural price. If there is a large supply and demand is low, the price will decrease below its natural price. This creates an ebb and flow of prices based on the product's supply and its demand in society. Eventually, an economic equilibrium will be reached (quantity supplied is exactly equal to quantity demanded). Of course, this is virtually impossible in practice due to ever-changing conditions and irrational and inconsistent agents.