A personal and scientific look at the experience of regret.

I spend a more-than-likely-unhealthy amount of time regretting past decisions. I think about past decisions that I made (or didn't make) multiple times a day, most of which make me criticize myself. I've tried to stop—or at least limit—this behavior, but it always comes back at some point. I try telling myself "there's no way I could have known", "you were just a dumb teenager", "some lessons have to be learnt that way". But I could have known, even as a dumb teenager, and some lessons don't have to be learnt in life. While some of those self-assurances are true and apply to some of my regrets, a majority of them were easily avoidable had I just taken some time to think about what I was(n't) doing.

In most cases, there is no way to predict what's going to happen. I can't tell when someone is going to die, or where/what I will be in 10 years, or what interests me. I can, however, mitigate the negative effects of the unknown. For example, we are all going to die at some point (fingers crossed for aging science to work out!), whether to natural causes (old age, disease, etc) or unnatural causes (accident, one's own fault, etc). Taking the step of opting to spend time with a loved one in lieu of other activities is one method of mitigation: knowing they will die eventually, possibly soon, and spending time with them. This behavior obviously borders on unhealthy and invasive. Life should not stop because of the small possibility a healthy 50 year-old may die. But as I discuss in my first major regret, there is little downside for doing so.

So while there isn't a way to truly know, one can know about not knowing, and take steps from there to prevent regret should the worst-case scenario occur.

Further, sometimes plain ignorance plays a role. Knowledge can be difficult to achieve, and while known unknowns are visible, unknown unknowns aren't, posing a threat.

I see three types of lessons:

I am content with learning all three lessons, depending on the severity. Number 3 more likely than not needs to be severe to get the point across. Number 2 need not be severe. Number 1 need not be severe nor even taught!

So when someone says something along the lines of "some lessons have to be learnt that way" in an effort to say "you shouldn't regret that, you wouldn't have learned it otherwise" and that lesson falls into category 1 or 2, I immediately stop listening.

Most people have similar thoughts with the occasional divergence from the norm. Regrets are included in these thoughts. I'll review some literature that examines regret.

Gilovich and Medvec (1995) published a wonderful paper on regret, The Experience of Regret: What, When, and Why, which asks the question: "How might we live our lives so as to keep the number and intensity of our future regrets close to some optimal level?" where regret is defined using Landman's 1993 book, Regret: The Persistence of the Possible:

Regret is a more or less painful cognitive and emotional state of feeling sorry for misfortunes, limitations, losses, transgressions, shortcomings, or mistakes. It is an experience of felt-reason or reasoned-emotion. The regretted matters may be sins of commission as well as sins of omission; they may range from the voluntary to the uncontrollable and accidental; they may be actually executed deeds or entirely mental ones committed by oneself or by another person or group; they may be moral or legal transgressions or morally and legally neutral. . . . (p. 36)

This definition is all-encompassing: it covers the dids and did-nots, the coulds and could-nots, the shoulds and should-nots.

Counterfactual thinking is a major contributor to regret:

This research begins with the observation that events are not evaluated in isolation, but are compared to alternative events that "could have," " might have," or "should have" happened. The work on counterfactual thinking has focused on two subtopics: (a) the rules by which counterfactual alternatives are generated (i.e., some alternatives to reality are more likely to be imagined than others) and (b) the consequences of comparing actual events with imagined events that might have happened. Much of the work on the consequences of various counterfactual comparisons has focused on the phenomenon of emotional amplification, or the tendency for people to react more strongly to those events for which it is easy to imagine a different outcome occurring. [These often include the words "if only" or "almost".]

As seen in my major regrets, they mostly fall under the action/inaction (why did/didn't I do that) categories, which is normal:

One way that individuals can arrive at the same outcome via counterfactual thinking demonstrates that the distinction between omission and commission has considerable hedonic consequences...people experience more regret over negative outcomes that stem from actions taken [action] than from equally negative outcomes that result from actions foregone [inaction].

This regret is short-lived. As time passes, the intensity tends towards zero. On the other hand, failures (inaction) follow some until their end of days:

When people are asked about their biggest regrets in life, it seems that they tend to focus on things they failed to do in their lives: "I wish I had been more serious in college"; "I should have told my father I loved him before he died"; "I regret that I never went to Europe." As troubling as regrettable actions might be initially, when people look back on their lives, it seems to be their regrettable failures to act that stand out and cause greater grief.

Prompting the obvious question:

What is it about the way people think about actions and inactions that makes failures to act more cognitively available in the long run and preserves their power to cause grief when the impact of regrettable actions has faded?

Our examination of these questions proceeds in three parts. First, we investigate whether, with time, people do indeed regret their failures to act more than their actions. Second, we review evidence indicating that this tendency is part of an overall time course in which actions are regretted more in the short term but failures to act are regretted more in the long run. Finally, we present a framework to organize the various psychological mechanisms that give rise to this temporal pattern to the experience of regret.

I have a few thoughts before Gilovich and Medvec answer the question (and before I look at their answers).

First, regrettable actions are more easily explained away. Lack of information, the heat of the moment, and cognitive biases can all play a role in taking an action. Using the authors' example from Kahnemann and Tversky's The Psychology of Preferences:

Mr. Paul owns shares in company A. During the past year he considered switching to stock in company B, but he decided against it. He now finds out that he would have been better off by $1,200 if he had switched to the stock of company B. Mr. George owned shares in company B. During the past year he switched to stock in company A. He now finds that he would have been better off by $1,200 if he had kept his stock in company B. Who feels greater regret?

(The consensus was 92% in Mr. George feeling more regret because he switched, rather than doing nothing like the Mr. Paul.) Over time, Mr. George can better explain his decision: he didn't have all the information to make a sound decision; given that it's the market, anything could have happened; etc. With long-term failure-to-do-X's, it's less easy to explain away. They had years, if not decades, to complete the action, yet never did. Any information missing could have been obtained in that time period.

Second, failures follow people throughout their lives, an unchecked box on life's to-do list. The Zeigarnik effect provides a possible explanation: "people remember unfinished or interrupted tasks better than completed tasks." Whereas completed tasks get thrown into the mind's recycling bin never to be recalled, the uncompleted remain.

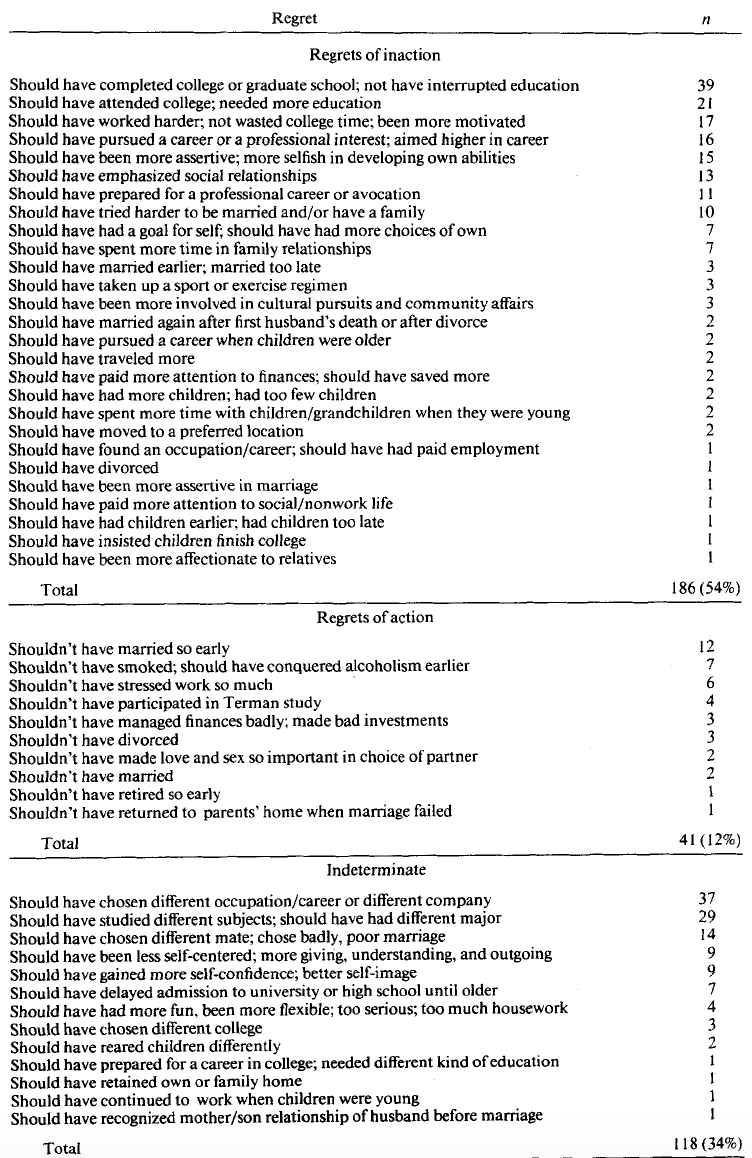

So, what do people regret most in their lives? A few studies gave one common answer of inaction, but Terman's studying of 720 people ("geniuses") with mean age 74 provides a more holistic answer, as seen below (table from here):

Terman's books can be found here for those interested:

It's important to note how diverse these responses are and to not blindly structure personal decisions based on this, e.g., "a lot of people wished they had finished college, so I should finish college!" Regrets, while often common, are still subjective and should be treated as such.

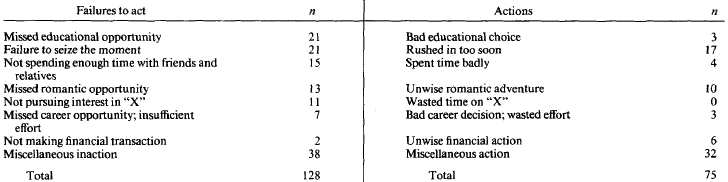

In another paper by Gilovich and Medvec (1994), The Temporal Pattern to the Experience of Regret,", they received 213 regrets from 77 respondents, as shown in the following table (respondent demographic below table):

10 professors emeriti at Cornell University, 11 residents of various nursing homes in upstate New York, and 40 Cornell University undergraduate students...16 clerical and custodial staff members at Cornell

In case anyone cries foul at the 40 Cornell students not being diverse enough, the 1994-1995 Annual Statistic Report on international students is available (I couldn't find much else on 1994 Cornell demographics).

A few takeaways from this result:

It is interesting that only 10 of the 213 regrets involved out comes caused by circumstances beyond the person's control. Thus, a sense of personal responsibility appears to be central to the experience of regret.

Regrettable failures to act outnumbered regrettable actions by nearly a 2 to 1 margin (63% vs. 37%).

A number of subsidiary issues were also examined. First, male and female respondents did not differ in terms of how frequently they mentioned regrets of action versus regrets of inaction. Second, there was some (not statistically significant) evidence that older individuals were more likely than younger respondents to regret things they failed to do. For instance, 74% of the regrets listed by our two oldest samples (the professors emeriti and the nursing home residents) involved things they did not do, as compared to 61% for our two youngest samples (the students and the staff members).

people's regrets reflect a trade-off between educational and career pursuits on the one hand and interpersonal relationships on the other: Those who spent time on interpersonal relationships regretted not achieving more professionally; those who spent time in professional pursuits regretted not devoting enough attention to friends and family.

no one regretted spending time developing a skill or hobby, even when the skill lies dormant and the hobby is no longer pursued.

When people look back on their lives, it is the things they have not done that generate the greatest regret.

While I still advocate not structuring personal decisions from specific examples, this does provide a broader overview that is helpful for individuals to implement. First, work-life balance needs to be found, where life can be in the form of relationships or hobbies (see next sentence). Second, no one out of the 77 respondents regretted pursuing their interests. Not a single one! This speaks volumes on the role passion plays in life satisfaction and fulfillment. Third, "it is the things they have not done that generate the greatest regret." This is, in a sense, a forewarning: if something is desired, make the opportunity to achieve it, else the regret will be great if it occurs.

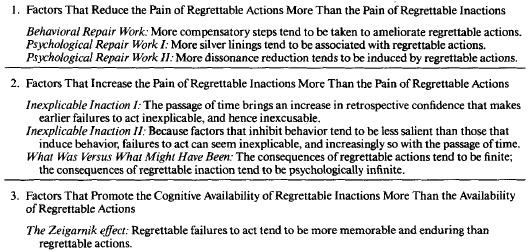

Gilovich and Medvec propose three mechanisms behind the temporality of regret (summarization table below):

First, there are those elements that decrease the pain of regrettable actions. Second, there are those elements that bolster the pain of regrettable inactions. Finally, there are those elements that differentially affect the cognitive availability (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973) of a person's regrettable commissions and omissions. These latter elements do not affect the intensity of regret over actions and inactions, but they do affect how often one is reminded of such regrets and therefore how often they are experienced.

(These factors are explained in more detail in the remainder of the paper, but not here. See the section titled Psychological repair work I: Identifying silver linings for the beginning.)

More literature on regret:

Eliminating regret altogether is virtually impossible, but reducing its future impact can pay great dividends on future happiness and satisfaction. I take lessons from the literature and my own experiences to form the plan I now use.

While future events can't be determined, some future feelings can. For example, sadness. I know (or am at least very certain) that I will feel great sadness when my mother dies. With this knowledge, I can form my behavior to mitigate the risk of regret in the future by spending more time with her, being nicer to her, etc.

The same concept applies to the so-called "failures" from the literature section. Looking in the future, will I regret not doing X? If there is a chance—the value of which is entirely subjective—then do it. Best-case scenario you would have ended up regretting it but will no longer; worst-case scenario you would not have regretted it, but still got the experience. This is somewhat contradictory to one of my biggest regrets, assuming you will be the same person in the future, hence the subjective chance.

Of course, life shouldn't be lived by analyzing every decision's regret potential before its made—there should be spontaneous adventures and split-second decisions. It's the big decisions that can last entire lifetimes or change who you are that should be checked before acting.

As the previous section's name implies, we are alike to a certain extent. This means that we are more likely to experience the common regrets of others, allowing a bit of planning to take place.

Both Terman's and Gilovich and Medvec's samples can be examined (keep in mind the sample demographics). Taking the ones with n values greater or equal to 10 results in:

| Regret (T or G&M) | Inaction/action | n |

|---|---|---|

| Completed college or graduate school; not have interrupted education (T) | Inaction | 39 |

| Chosen different occupation/career or different company (T) | Indeterminate | 37 |

| Studied different subjects; had different major (T) | Indeterminate | 29 |

| Should have attended college; needed more education (T) | Inaction | 21 |

| Missed educational opportunity (G&M) | Inaction | 21 |

| Failure to seize the moment (G&M) | Inaction | 21 |

| Worked harder; not wasted college time; been more motivated (T) | Inaction | 17 |

| Rushed in too soon (G&M) | Action | 17 |

| Pursued a career of a professional interest; aimed higher in career (T) | Inaction | 16 |

| Been more assertive; more selfish in developing own abilities (T) | Inaction | 15 |

| Not spending enough time with friends and relatives (G&M) | Inaction | 15 |

| Chosen different mate; chose badly, poor marriage (T) | Indeterminate | 14 |

| Emphasized social relationships (T) | Inaction | 13 |

| Missed romantic opportunity (G&M) | Inaction | 13 |

| Shouldn't have married so early (T) | Action | 12 |

| Prepared for a professional career or avocation (T) | Inaction | 11 |

| Not pursuing interest in "X" (G&M) | Inaction | 11 |

| Tried harder to be married and/or have a family (T) | Inaction | 10 |

| Unwise romantic adventure | Action | 10 |

My takeaways from this data:

A few general, obvious suggestions can be made from this data:

Below is an incomplete list of my regrets in no particular order. Hopefully someone who reads this can learn from my mistakes and apply it to their own life. The lessons I wish to pass on come after the bolded "Lesson" in each item.

Regret: Not spending more time with my parents during my six-month summer vacation before starting full-time work.

I was sent home from my final semester of university in March 2020 due to COVID-19 and started full-time work in September, giving me six months of free time to do whatever I pleased. I spent it writing this website, reading, exercising, playing video games with friends, and mindlessly browsing the web. Days flew by, as did the weeks and months. I did spend time with my parents, though. We spent evenings together during the initial stage of the pandemic and went on the occasional dog walk in the woods. I rode mountain bikes regularly with my father on our home trails. And then my father died unexpectedly the week after I moved 5 hours away for my new job.

There was no telling that was going to happen, no indicators or forewarnings, which gives me a partial excuse. After all, you can't spend your life thinking this is the last time I could see this person, I should spend most of my waking hours with them. It's unrealistic and unhealthy. And yet, I could have done more. I could have put down the video games and gone to watch television with them. I could have said yes to more walks instead of reading. I could have said yes to more mountain bikes rides instead of [insert less meaningful activity here that I could do anytime in the future while away from my parents at my new job].

I knew I would be gone in September, only coming home to see them every 1-3 months during the holidays and a spontaneous weekend trip, but I still chose to spend my time on activities that were doable anywhere at anytime, a category that spending time with my parents does not fall under. And I will be forever racked with guilt for this, forever blaming myself for not doing more.

Lesson: Prioritize activities that aren't always available (e.g., experiences, spending time with family/friends) over those that are (e.g., media consumption, exercise). Ideally, these can be combined.

Regret: Thinking my future self would be identical to my current self, causing doors to be closed.

Some doors are only open for a specific period of time, others become more difficult to open, and others remain open all the time. I made the mistake of planning my future around my current self's interests and plan, not taking into account that my interests could radically change. This causes one big issue: Time can be wasted delving into interests that have small likelihood of paying out, where that likelihood is only meaningful if you spend a significant amount of time on the interest. For example, wanting to become a musician for a living requires hours and hours of practice while the likelihood of "making it" remains unfathomably small. Hundreds of hours spent on something for "no" return. (A few notes on this point, as I'm sure some readers will disagree. 1) My current risk tolerance is rather low, hence my advocating for putting eggs (interests) in different baskets (time devoted to each). 2) There is not necessarily no return. You probably had fun, met people, developed some valuable skills, etc., but in the end the ultimate goal did not come to fruition. 3) You never know what will happen. While that shouldn't deter you from following a dream, you should be practical in its pursuit and understand the probabilities associated with reaching said dream.)

My year review process helps me to keep track of how I change throughout the years.

Lesson: Don't assume you will be the same person in X years. Interests and circumstances change regularly, and you should be fluid with them.

Regret: Not spending money and missing out on experiences.

Life is to be lived for experiences and money is a means to an end (experiences), not a means unto itself. When I was younger, I was stingy with money—not frugal, stingy. I would eat at home before going out with friends, opted out of multiple road trips partially due to wanting to save money (among other reasons), and so on. As demoralizing as it is, money is often the gateway to experiences. While I have bumped my mindset up a rung to the "frugal" category, I am much more liberal about putting money towards experiences and good causes. Frivolous purchases remain off of my list.

Lesson: Spend money towards experiences. The money will not be missed in years to come.

Regret: Not enjoying childhood (up to end of college) more.

In 8th grade, I spent the entire year training to set the school's 1600 m run record. I went to bed around 8:30pm, woke up at 4:30-5:00am to train, then did it all again the next day. I got around two hours of free time every night after getting home from basketball practice, but these were tediously spent on homework I wasn't able to finish in class. I declined sleepover invitations because I needed the sleep for recovery, which in turn sacrificed friendship development. Grades 9-10.5 (as in up to the first semester) weren't much different. I ran cross country and track, which required similar bedtimes and wake up times. I had more fun during these years, but not as much had I not participated as seriously (not participating at all would leave me primary-friend-group-less, bringing the fun much closer to zero). Grades 10.5-12 were more fun, but at the cost of poor choices. Grades 13-16 (university years) were spent studying for good grades and working for good experience. These years I don't regret as much as the other ones: they mattered much more than the others. My grades and job got me an internship at the powerhouse company I now work for full-time and I thoroughly enjoyed my job. It's the earlier years that I regret not taking more advantage of.

My adult life now consists of waking up around 4:30am to exercise, working from 7:00am-4:00pm, then going to bed at 9:00pm: a total of 5-6 hours of free time per day, depending on sleep. While I do enjoy this schedule and it gives me time to pursue hobbies, I always wish I had more time. This figure emphasizes the importance of finding a fulfilling career.

All this is not to say you shouldn't pursue your passions. You should and with vigor if it means a lot to you. But it shouldn't come at the cost of relationships and experiences if it won't be life-lived (once again, there's a probability of success that should determine if you want to continue on that path). Most high school sports players won't go on to play in college and thereby shouldn't sacrifice other aspects of their lives for it.

Lesson: Enjoy the period in your life that isn't consumed by responsibilities or busy time. Sadly, this appears to be only childhood and retirement, one of which is gone never to return, the other many years away. Take the occasional step back and see if what you're doing is bringing as much value to your life as you'd like, and if not, what you can do to improve that.

Regret: Not being kinder to people, especially family members.

Kindness should be the default interaction type with anyone. Anger has its use—it's naive to say it doesn't—but those cases are wide and in-between. I tend(ed) (both past and present tense, I'm working on it) to resort to the offensive when disagreeing with people. Some would interpret my tone as condescending and my questions belittling when they weren't: they were aggressively inquisitive. I should take a step back, understand their perspective, then respond with patience and kindness.

My default approach of aggression has soured relationships I am still working on repairing. Even though the offended know I am not meaning to come across as condescending or rude, it's hard to not hear it that way and I understand and respect that.

Lesson: Default to kindness when talking with someone. Attempt to understand their perspective before turning to aggression.

Regret: Not taking more pictures.

My father was huge on taking pictures. At the end of family outings he'd hit us with the inevitable "line up [for a family picture]" and go find an innocent passerby to take the picture. My brother and I would groan as we begrudgingly got shoulder-to-shoulder and smiled at the flash. This mindset diffused into my personal life. I didn't take many pictures with friends or while I was having fun. It wasn't until years later when browsing through old family pictures that I realized their value. They capture the moment and provide a better memory than you can put together on your own. The scenery, what everyone was doing, how they were feeling. Some pictures don't have it, but most do, helping to transport you back in time to that moment.

I now try to take pictures at any opportune time: selfies, group, it doesn't matter. I have way more to look back on than I did before.

Lesson: Take more pictures, whether it be with/of friends, an activity I'm doing, or anything else.

In January 2021, I created Anki cards to instill the thought patterns. I review each regret-lesson pair daily as a reminder.